Report, C-01

“. . .Our song is a bird calling out like a jingle:

how beautiful you make it sound!

Here, among flowers that enclose us,

among flowery boughs you are singing. . .”

![]()

![]()

![]()

Floating Gardens for a Sinking City

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fragment of Diego Rivera’s “La Gran Tenochtitlan”, 1945.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

An Interview with Elena Tudela on Xochimilco, Water, Food and Waste in Mexico City

Elena Tudela is an architect at Urban Planning firm O-RU, and educator at UNAM in Mexico City. As part of her work-in-progress at O-RU, Elena is actively working towards the revitalization of Xochimilco in today’s Mexico City.

AO

ET

AO

ET

A Vermicular Foundation

“. . .Our song is a bird calling out like a jingle:

how beautiful you make it sound!

Here, among flowers that enclose us,

among flowery boughs you are singing. . .”

Floating Gardens for a Sinking City

Fragment of Diego Rivera’s “La Gran Tenochtitlan”, 1945.

An Interview with Elena Tudela on Xochimilco, Water, Food and Waste in Mexico City![]()

Elena Tudela is an architect at Urban Planning firm O-RU, and educator at UNAM in Mexico City. As part of her work-in-progress at O-RU, Elena is actively working towards the revitalization of Xochimilco in today’s Mexico City.

AO

We are interested in the way your work addresses the history of water in Mexico City, and because of the nature of it, it also relates to waste management in food in some way or another. Could you explain how these issues converge in the city?

ET

Let me think about this, yes... I mean, there's a lot of interesting points of convergence between food, water and waste in the city. If you find a place where those convergences are interesting, that's better than trying to understand the whole city as a system, or focus on one of the areas where these express themselves clearly.

So, the Valle del Mezquital, obviously, it's a huge deal, because basically we send all our sewage up there and they're using it for irrigation, for things (food) that shouldn't be irrigated with non drinkable water. Which means it comes back to us in the form of food that has metals in it. So it needs to be really washed so that it can be consumed. Part of the impact of that system has to do with the health implications of it.

There's a lot of water going out from the city, A LOT, and there's a lot of very interesting things about Valle del Mezquital, the Otomies and other indigenous cultures that have been doing agriculture since forever in that place, and they have a and they have a in interesting point of view of what that area is for them, that suddenly links us in a way that people are interested in understanding a bit better.

Theirs is a very small scale form of practice that suddenly has everything to do with the largest food system in the country, so that has brought these communities into the spotlight.

But there's also all of the implications of the water that’s been used to irrigate those crops across decades that is so interesting, because it is actually producing a new aquifer that for some reason, the ground’s composition in that area it’s cleaning the water. So they are discovering new aquifers due to the huge volumes of water that we’ve thrown into that area, that's actually much better in quality. So there's a line of research that, in a very twisted way we are cleaning water without knowing.

But all of these implications of our very weird system, because honestly, our management of water is quite terrible. We need to change the way we manage water in so many ways. One of them is understanding our link to that area of the metropolitan area: where our food comes from.

And within that system in terms of food, the Central de Abastos, which is the largest market and distribution center in Latinamerica. There are a lot of people, it is a huge economic system.

Things sold and produced in coastal regions, are sold there first. So it's like a connecting point that has its own water treatment system, and on top of that, it has one of the largest roof surfaces of the city that could be potentially used for water harvesting. You still need to store and manage that water, but that economy could actually allow for that to happen. It is located in Iztapalapa, one of the poorest areas within Mexico City, which is one of the areas with the biggest water shortage issues. So it is a really interesting place that connects with many issues at the same time.

Another place that brings forth these issues are Xochimilco and Milpa Alta. Milpa Alta has agriculture, extensive, very regular agriculture. But it's one of the few areas of the city that actually still does that, Milpa Alta is our rural-urban district.

But then Xochimilco, is a whole other dimension. I think Xochimilco is one of the most interesting cases in the city, mainly because it's one of the remains of the lakes. I mean, there's other lakes like Chalco and Zumpango, but Zumpango is part of the sewage system. It's actually just like open sewage.

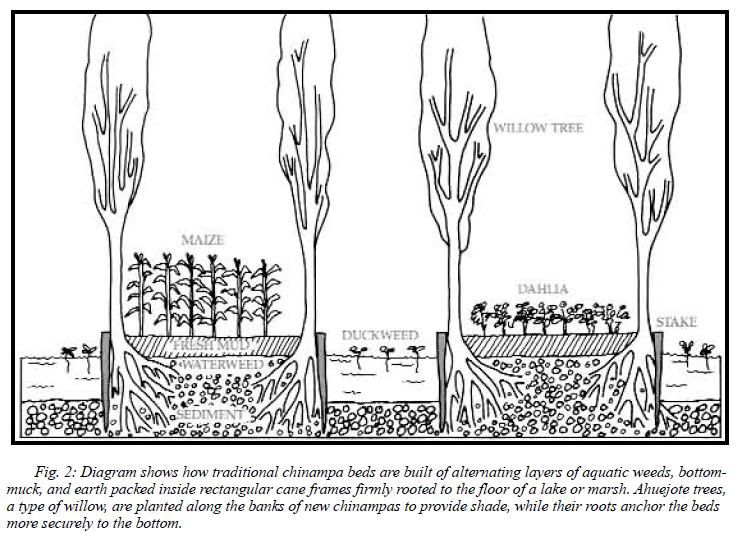

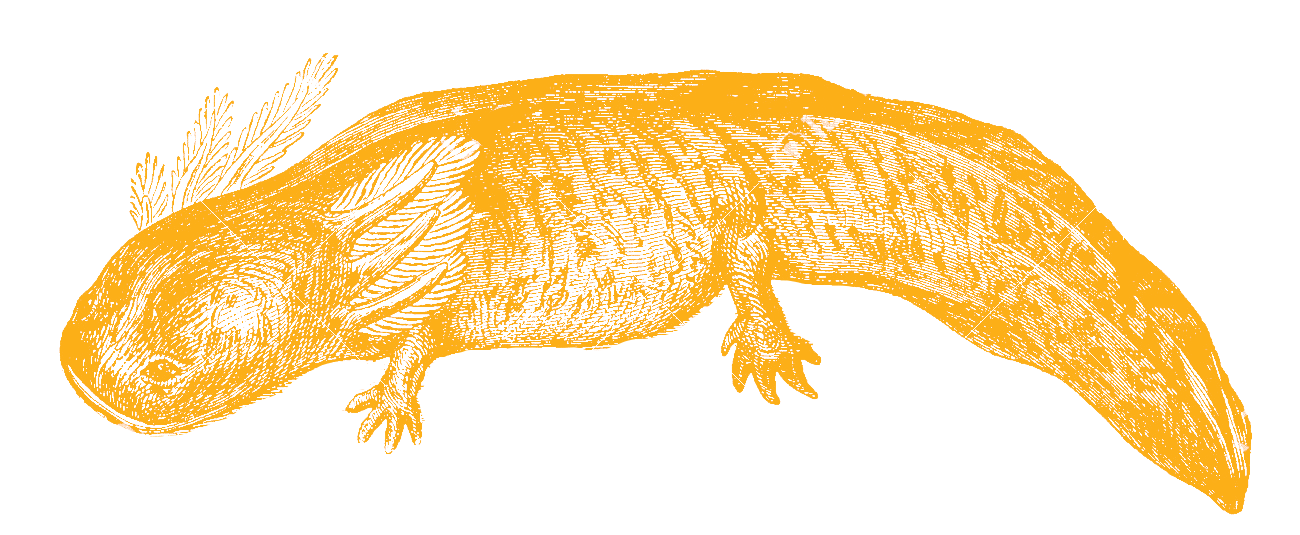

Xochimilco and Chalco are part of a larger, more complex system, social and environmental. We worked on the Masterplan for Xochimilco two years ago. Now I'm finishing a project on the rescue of the Axolotl species with a system that's very interesting that we are thinking, might save the chinampa system from disappearing. What's most interesting is that the Chinampa system, it's been the only thing that’s here since before the Aztecs. So it's the most resilient thing, but it's also the most vulnerable right now on. It's a great invention. It's not the only place where this has been done before, but it's where it’s been most effective and more polished, and it's probably one of the few places where it's still being done

It’s social organization follows a very traditional familiar structure and from generation to generation they pass on the knowledge. The chinampa system is one of the main reasons why Tenochtitlan became the largest population in the world back then, and it was because they had availability of food right here.

It's a system that is only done in wetlands or in very shallow lakes, like the ones we had in Xochimilco and in Tlahuac. So it's very interesting because it even has its own culinary culture that is quite unique. Have you ever heard of Tlapique? It’s like a fish. They cook it with a lot of herbs. It's so delicious, and it tastes like nothing that you've tasted before. I mean, it's a very prehispanic dish, it is a very special and unique combination of herbs. They have all these recipes and all of this culture that is amazing. But now they work as a cooperative and UNAM, which are the ones that hired us from the Institute of Biology to develop a system where they can use organic fertilizers, and updating the whole system, adding bio filters at the beginning and the end of the canal of Chinampa Refugios.

A Chinampa Refugio allows for Axolotls to grow back, the water changes color, the soil becomes really fertile, and it’s free of pesticides, fertilizers, etcetera. So the food grown there is really high quality. So they're starting their own Sello Chinampero (Chinampa Brand), for instance, where several high end restaurants are starting to ask for products that come from Chinampas. They're within the city and they're sold, obviously more expensive, but there's a market for it, and so all of a sudden it's not about urban agriculture. It's more about a resilient system that provides for a whole other ecosystems to exist while protecting the land from urban development, which is actually putting a lot of pressure on Chinampas.

AO

Is it a high volume of production of food in the chinampas?

ET

Very! They're using their land non stop. It’s a prehispanic tradition, but obviously it's being updated. So there's a lot of innovation into the technology itself. The idea is genius from the start: you don't need irrigation, it'd be aired enough so that water would flow. The system needs a really specific tree, the ahuejote, because its roots are deep and work as foundations holding the ground together as they provide shade for the crop. So it's a perfect system. It's amazing, it was really well designed.

And they polished it so much, but with modern development, many of the people of the area don't know how to do it anymore. They sold their lands or they are using it, like for football fields. But some have been very smart and resilient towards the demands and trends in the market.

They're like “Awww, you call this baby something, baby carrot, baby, whatever? This is just the sprout. Why do you call them, baby? What is wrong with these hipsters?” haha, it is funny.

So in Mexico City we do have agriculture, and it's not urban. It's quite rural, within urban land. I mean, it has a denomination of rural settlement and it is half of the conservation land that borders the whole city. Half of that is used for agricultural purposes. So mainly near Milpa Alta. So in a way talking about urban agriculture in a city that actually has agriculture, But we never talk about it in those terms. Chinamperos are trying to protect a tradition that actually provides ecosystemic services: it protects wetlands! But some people are using the canals as landfill to sell for real estate development. Which is terrible.

So instead of making use of the canals for mobility, which could be used as that in an area that's very deprived of communication infrastructure, and it was very visible during the last earthquake, it was so hard to get there and Iztapalapa and Xochimilco are both located within what used to be like the edge of the Lake, which means there's, geologically speaking, It's like part lake, part transition zone and part slope, area, and that's very vulnerable to cracks, you know, geological problems.

So during the earthquake, they needed a lot of help and nobody could get there. Which could make canals a very interesting way of moving, as it used to before.

The new government (I have no idea at what point they are right now with that project, but) is working on Canal Nacional which is this infrastructure that brings water from the water treatment plant of Iztapalapa-Cerro de la Estrella like the only mountain in Iztapalapa in the middle of it, and it's bringing water to Xochimilico, it is wastewater but it's good quality waste water, It has no industrial residues, so it's water that can be used for irrigation in a good way and still provide good quality crops.

Before water came from the mountains. But now that they’ve developed all that area, water comes from the water treatment plant, one of the largest in Mexico. But there's water for it. There will always be water in Xochimilco, because there's a lot of waste, like sewage being treated, so much, the only water we can rely on it’s probably waste water.

***

![]()

‘La gran Tenochtitlan en 1519”, painting by Miguel Covarrubias, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City.

![]()

Nuremberg Map of Tenochtitlan, 1524, from Hernán Cortés’ Second Letter. Courtesy of the Newberry Library, Chicago.

![]()

"Mapa Santa Cruz" - Indigenous Representation of Mexico’s Central Valley, 1541.

***

‘La gran Tenochtitlan en 1519”, painting by Miguel Covarrubias, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City.

Nuremberg Map of Tenochtitlan, 1524, from Hernán Cortés’ Second Letter. Courtesy of the Newberry Library, Chicago.

"Mapa Santa Cruz" - Indigenous Representation of Mexico’s Central Valley, 1541.

***